“Her class is sooo boring!”

“Yeah, and she’s always in a bad mood.”

When I was an assistant principal at a middle school, I had asked two students to come hang out in my office and tell me what was going on in their eighth grade French class. And tell me they did.

“We do the same thing every time. And I think she hates us!” The students went on to paint a very bleak picture of what was happening in their class. I asked them if there was anything they could be doing differently.

“Well, yeah,” they both sheepishly replied and confessed that they were constantly goofing off as a result of how disengaged they were from the class.

Flashback to a week earlier when I had been chatting with said French teacher, and she painted a very similar picture.

“It’s become pretty toxic in there,” she told me with a look of both exasperation and desperation. She had had this class since they were sixth graders, when she was a first year teacher. During our conversation, she was able to acknowledge that she had struggled with classroom management and student engagement when she first started teaching (as the majority of us do!). And, over time, a negative climate had taken hold of that class.

I knew just the thing that would help. “Let’s run a circle,” I said.

WHAT ARE RESTORATIVE PRACTICES? WHAT ARE CIRCLES?

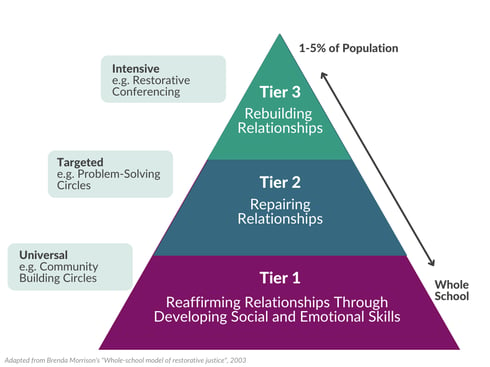

Restorative practices are a range of approaches that aim to develop community and to manage conflict and tensions by repairing harm and restoring relationships (Costello, Wachtel & Wachtel, 2013). When l was a middle school administrator, we not only utilized a continuum of approaches, from affective statements and questions to impromptu conferences, circles, and formal conferences (McCold & Wachtel, 2001), but we also categorized our circle practice into tiers.

In this hierarchy of restorative responses (Morrison, 2004), tier 1 circles are universal and center on re-affirming relationships through building social and emotional skills. At our school, tier 1 circles focused primarily on community building or academic content and were utilized in our Advisories, core academic classes, and specialty classes.

Tier 2 circles are targeted and focus on repairing relationships in classrooms or groups. Our tier 2 circles were run by either our trained counseling team or me in a whole classroom setting or with small groups; the circle I ended up running with the French class described above is an example of a tier 2 circle.

Lastly, tier 3 circles are intensive and center on re-building relationships via conferencing and mediation. When I was an administrator, staff were able to request that I run a restorative conference with them and a student at any time during the school year. Depending on a particular situation or incident, I might also recommend to staff or students that a restorative conference would be beneficial.  Whole-school model of restorative practices (PDF)

Whole-school model of restorative practices (PDF)

TIPS FOR CIRCLES

We built our restorative practices program at our middle school over the course of several years. As circle practice, in particular, became increasingly embedded into our everyday school culture, several points became clear:

Circles Take Trust

One of the most powerful things about circles is that they give a voice to the voiceless. All too often, student voices are set on the back burner, if they even have a place at all. With circles, students have the opportunity to develop a sense of agency and to feel empowered. However, in order for students to feel comfortable enough to share candidly, a sense of trust has to be built with not only their peers but also with the adult running the circle. The two young people who were able to tell me about what was going on in their French class were able to open up to me because I had built a relationship with them over the course of their middle school years. What's more, I also had positive relationships with the rest of the students in the class, and that was instrumental in terms of the students letting themselves be vulnerable enough to share about the issues in their class when we held our circle.

Circles Take Willingness

When I give presentations on restorative practices and talk about examples of circles in which students openly discussed some pretty serious issues, or when I mention how staff members took ownership over their own mistakes in front of a classroom full of students, the reaction can sometimes be one of incredulity. Yet it’s important to remember that one of the keys to a productive circle is a willingness on the part of all parties to engage in an honest, respectful dialogue. More specifically, willingness on the part of the adults to be open to critical feedback and to making changes in their practice is absolutely crucial. If there is resistance from a staff member, a tier 2 or 3 circle should not take place. If we think back to that French teacher, if she had scoffed at the idea of listening to student feedback and taking ownership over her own mistakes, there’s no way the circle would have been successful.

Circles Take Work

Perhaps surprisingly, one of the biggest obstacles to successfully implementing circles is simply all of the planning and logistics that are involved. For instance, staff might want to set aside part of their class period for tier 1 community building circles, but carving out time against competing interests can often be difficult. Or take how, to the untrained eye, a seamless tier 1 circle may look like a simple icebreaker activity. However, those who have implemented circles with fidelity are all too familiar with the hard work that is involved in establishing norms, building a positive classroom culture, and deciding on the appropriate prompts and circle activities that best meet the needs of their particular cohort of students.

When I ran tier 2 and 3 circles, it was sometimes a Herculean task to find a day and time that worked for a specific class or teacher’s free period against my own packed schedule. There’s also all of the pre-planning that goes into creating discussion round questions (in conjunction with the teacher) as well as the meetings I held with certain students before the circle to gauge what might be expected and what students might say. What’s more, if the circle ends up being scheduled too far down the line, it might lose its connection to, and therefore its impact on, the event or events that triggered the circle in the first place. In short though, if we truly value the restorative nature of circles, we prove it by putting in the work to make them happen.

Circles Take Time

After wrapping up a targeted tier 2 circle with a class, I always remind both the teacher and students that a 45-minute discussion is not going to suddenly change or solve things overnight. It is simply the first–not the last–step in a cooperative, ongoing process. And this process needs time to play itself out, to allow space for minor setbacks, and to give students opportunities to regroup and make progress.

So, you might be thinking, whatever happened with that French class?

I scheduled a follow-up circle about a month after our first circle, but I knew it was important to give the class the time and the space to let things play out. When I eventually returned for the follow-up circle, I could sense a change the moment the students walked in. Instead of dejectedly sitting in their seats with scowls on their faces, the students bounded into the room and were happy to report that not only had the students stepped up in their attitudes and behavior, but the teacher had also implemented many of the suggestions that they had given her. While they acknowledged that there were still some improvements that could be made, the students and the teacher expressed how much more enjoyable the class was and how they felt that they were learning even more academic content than before. This roomful of engaged learners and one very satisfied–and relieved!–teacher was a clear testament to the transformative power and restorative nature of circles.

.jpg?width=300&height=169&name=Blue%20Orange%20Fitness%20Workout%20Cool%20Presentation%20(1).jpg) Continue your learning. Discover how to design and implement circles through the lens of UDL to help all learners grow and succeed.

Continue your learning. Discover how to design and implement circles through the lens of UDL to help all learners grow and succeed.

This post has been updated from it's original publishing date