If research shows we are products of our environments, why aren’t we doing more to create learning environments where all students can be successful?

By Steven Van Rees and Katie Novak

It is no secret that some stakeholders are not supporters of inclusive education, despite the evidence-base on its effectiveness. The challenges of remote and distance learning have only compounded fears for some that inclusive education is simply not possible.

But what if simply creating the right conditions would allow teachers to provide a diverse set of students – with varying strengths and weaknesses – equal opportunities to be exposed to rigorous educational standards and succeed? What if that even made the planning process for shifting in person/remote settings even easier?

When creating a safe, accessible, culturally sustaining, trauma-informed and linguistically appropriate inclusive environment, start by implementing Universal Design for Learning (UDL), a research-based framework that helps teachers address the academic, behavioral, social, and emotional needs of all learners. Doing so can help educators create dynamic and equitable learning environments so that all students have authentic opportunities to learn to their capacity in meaningful, relevant, and authentic ways.

In UDL classrooms, all students, regardless of variability, are together (whether in person or in the virtual space), and are guided to reach high expectations and engage in productive struggle. Educators help students embrace their individual strengths and foster collaboration and community to ensure that all students work together, motivate each other, and build integrative thinking skills. These conditions of nurture are critical foundations of an environment that will meet the needs of all students.

In order to establish this kind of learning environment, it’s critical to examine the classroom environment through three distinct lenses: the intellectual, physical, and emotional.

The Intellectual Environment

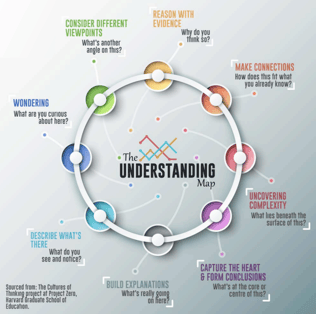

Creating a healthy intellectual environment involves identifying how students can not just retain, but also use the information and ideas presented in a lesson. One way to promote rigorous thinking is to support students as they examine content from various angles, allowing students to dig into the multiple dimensions that every rich topic or issue holds. Harvard Graduate School of Education and Project Zero Principal Investigator Ron Ritchhart identifies eight possible ways for students to develop an understanding of a topic so that genuine thinking serves as the underpinning of a lesson or unit. In his Understanding Map, Ritchhart provides us with a visual representation outlining the kinds of thinking needed to create lasting meaning. Students in Jessica Gentile’s grade seven ELA classroom at Mill Creek Middle School in southern Maryland use the Understanding Map as a tool to navigate through arguments. Many students in her class struggled throughout much of the school year engaging with complex text. Gentile shares. “It only took a few tries with the Map for the students to take off on their own with it. What I want is for kids to have a way into texts without my constant prompting. I want independence for them.”

After dissecting texts using the elements of the map, students are able to participate in meaningingful, collaborative discussions with their peers (whether in person or via Zoom!), employing the language of the map as a guide. “It’s easier to know what a writer is saying when we look for certain things like facts to back up claims or how the writer makes connections between ideas,” one of Mrs. Gentile’s students remarks. “The map makes it fun to peel the fruit!”

As students become comfortable with using the map as a scaffold, they become less dependent upon the teacher. This allows them to become expert learners, the goal of Universal Design for Learning. An expert learner is a student who is motivated and purposeful, knowledgeable and resourceful, and strategic and goal-directed.

Physical Environment

When organizing a classroom’s physical space, it might be best to consider how it can serve to support the intellectual environment but in this day and age, there are also some important health considerations we must be aware of. If it is felt that students often learn more effectively when discussing a topic or issue, then collaborative tables, chairs, or rugs can be put into place. During a pandemic, that may not be possible without clear partitions. You may also want to consider taking the discussion groups outside, where students have more space to spread out and be socially distanced (while also getting some fresh air!) If your learning is remote, think about how the “physical space” of the virtual world can be set up to foster community and collaboration. Use breakout room features, connect students with one-another offline, and encourage group work with classmates, “viewing parties” for class presentations, or collaboration via Facetime.

It is important to note that a flexible physical classroom acknowledges that not all students will benefit from the same options. Designing a learning environment through the lens of UDL will mean that students have options and choices to meet goals within a physical space that adapts to their interests and needs. We understand, this is easier said than done right now in the physical world, but try to see where you can get creative while still providing physical distance.

Allison Saul has led both elementary and secondary students for almost twenty years. Experience informs her flexible classroom design. In her seventh grade english classroom at Windy Hill Middle School, students typically sit in grouped tables. All students have a clean line of sight to the front board. The anchor charts and student work on the walls serve not as decoration, but as reminders of the learning that takes center stage; of what is valued.

A poster centered prominently in the front of the class asking students “What am I Learning and Why?” provides another visual cue that informs students of the importance of their time in the classroom. “My room isn’t the location of a design show. Sure, I want to make it look nice, but what I really want is the room to work for the kids,” Saul shares with a smile.

Emotional Environment

We’ve heard that most students won’t remember what you taught them, but they will remember how you made them feel. The connections between the affective and cognitive domains are great.

When a student experiences a threatening or stressful situation, cortisol levels in the brain rise. Elevated levels of cortisol are associated with reduced memory and cognitive function, and studies have shown that children who live in continual states of distress, including those in poverty, experience long-term increases in cortisol, frequently resulting in cognitive and developmental delays (Suor, 2015). Reducing stress through universally-designed instruction is a valuable starting point to help students in feeling like they matter, that school is something for and with them not something done to them. This can be particularly challenging in remote settings, when students may lack access to technology or need to help care for siblings, but that makes it ever more important.

Educators need to provide options for student self-regulation, where there are options for students to learn to cope when they are frustrated, overwhelmed, or are experiencing trauma. For example, teachers can provide differentiated models, scaffolds and feedback for managing frustration, seeking external emotional support, developing internal controls and coping skills, appropriately handling subject specific phobias and judgments of “natural” aptitude (e.g., “how can I improve on the areas I am struggling in?” rather than “I am not good at this”), and using real life situations or simulations to demonstrate coping skills (CAST, 2018). Some learners may not have access to these items at home, think about what you can send to them – a classroom in a box.

The classroom organization, as well, reveals much about our desire to see our students thrive. When we offer students varied tools to reach their learning goals, configurations that respect the need to talk, listen, and question ideas with their peers, and visual displays of student thinking, tacit yet powerful messages are sent to our students that we are indeed invested in their wellbeing.

Why Bother?

Thinking about the three legs of a class environment may seem challenging. However, if we agree with Lev Vygotsky, the influential Russian developmental psychologist, that “children grow into the intellectual life around them,” then we are doing the best thing for our students when we consider the environment as we develop our lessons.

Dive deep into UDL and improve your practices. Explore our self-paced and facilitated courses.

Steven Van Rees coordinates UDL efforts to support student learning in Calvert County, Maryland. He is a faculty member at Harvard’s Project Zero Classroom Institute. Since 2007 Steve has served as an instructional coach for the courses Teaching for Understanding, Leading for Understanding, and currently Creating Cultures of Thinking through the Harvard Graduate School of Education. In 2012, he was named as a fellow at Harvard’s Project Zero Future of Learning summer institute. Steven also teaches graduate courses in curriculum analysis at McDaniel College and has been on the faculty of the Washington International School Summer Institute for Teachers: Connecting DC Educators with Project Zero Ideas. He is passionate about making student thinking visible in the language arts classroom.

References

- Anderson, M. (2016). Choosing to learn. Learning to Choose. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- CAST. (2018). UDL Guidelines. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org/engagement/self-regulation/coping-skills-strategies/coping-skills-strategies

- Ritchhart, R (2015). Creating Cultures of Thinking. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

- Suor, J.H., Sturge-Apple, M.L.,, Davies, P.T., Cicchetti, D. &, Manning L.G. (2015). Tracing Differential Pathways of Risk: Associations Among Family Adversity, Cortisol, and Cognitive Functioning in Childhood. Child Development, 86(4):1142-1158.

- Unger, C. (1994). What teaching for understanding looks like. EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP, February 1994, 8-10.