- Galileo Galilei used physics, astronomy, and mathematics to develop the telescope because he wanted to understand the solar system.

- Katherine Johnson ran key computations for trajectory analysis to understand satellite orbital paths.

- Maryam Mizakhani used the geometry of curved spaces to explain straight lines across curved surfaces, ultimately impacting our understanding of the behavior of earthquakes.

When we think about the jobs that don’t exist today - the jobs that will help answer questions and solve problems - they will all be connected to science and mathematics. But in order to be ready to ask and answer these questions, our students need to see, experience, and make sense of the math all around them.

By cultivating a safe and flexible learning space where students feel valued and supported, we enhance their motivation to actively participate in mathematical discussions and problem-solving, making the learning experience more enjoyable and meaningful for everyone involved. It is our responsibility to have a relationship with our students, to understand their held identities and experiences, and illuminate how mathematics can help them understand the world around them. Through Universal Design for Learning (UDL), we can co-create a learning environment where our students develop learner agency - where they are self-aware and self-directed and are able to succeed in really flexible and adaptable environments.

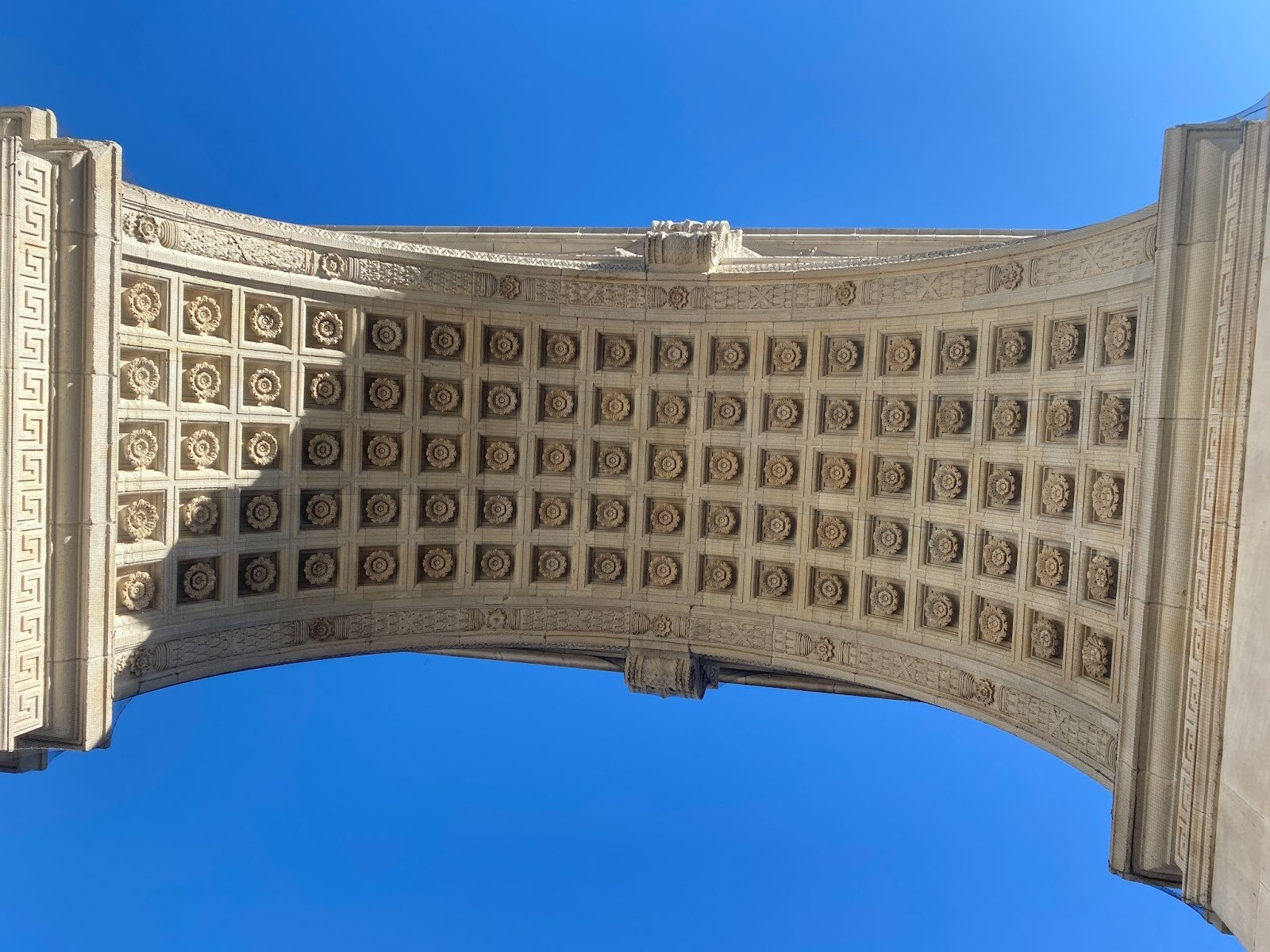

One critical technique to consider when co-creating the learning environment, specifically related to engagement, is creating opportunities for students to see the world they live in in the math they are doing. Here are three ways to bring the world into your math classroom:

Bring visual images from around your community into your classroom

In our book, Universal Design for Learning in Mathematics Instruction K-5, Katie Novak and I share the power of a launch at the beginning of a math lesson. A launch is a daily number sense routine, used in the first 5-15 minutes, focusing on purposeful, discussion-rich learning opportunities. The goal is to encourage all students to engage in mathematical thinking while promoting a sense of belonging. We can ensure the launch is as welcoming and inclusive as possible when we use images from our local community or images from around the world. We promote discussion with open-ended questions like, “Which One Doesn’t Belong?”, “How many and how do you know?” “What’s the same and what’s different?” Through this type of discussion, students not only engage in thinking about the world around them through a mathematical lens but simultaneously engage in the mathematical practices that they will need to use in their discussions throughout the remainder of the lesson. Over time, I’ve found that students start bringing in their own photos, books and mementos to discuss with their peers.

Use children’s literature as a relevant context

In many elementary classrooms, we find that literacy and mathematics are taught in isolation. Unintentionally, we send the message that there is no mathematics in the books we read and no real comprehension of the mathematics we do. This may be true in a math classroom that only focuses on procedure and calculation. But in a math classroom that wants to promote problem-solving, reasoning and metacognition - comprehension is critical. Comprehension requires making sense of a problem and root it in context. Students are far more readily able to comprehend a math problem when it is rooted in a context that makes sense in their world. In our book, we share an example of a problem asking students to solve a problem involving a person with 93 sheets of paper and another person with 57 sheets of paper - asking the students to solve for the total number. This context posed the question - why do they know exactly how many sheets of paper they have? At the time, it was a very silly conversation in my classroom. In reality, though, this was not a question my students were interested in pondering, nor a question that seemed even remotely realistic.

In contrast, posing a question related to a book we are reading together ensures all students are included in a relevant and meaningful context because we are all reading the book together. In her essay, “Windows, Mirror and Sliding Glass Doors,” Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop focuses on the importance of children seeing themselves in the books they read. Her research and teaching on multiculturalism in children's literature help us understand that diverse books could help break down stereotypes, biases, and prejudices (Bishop, 1990). In our classroom, we can consider diverse books that provide these windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors for our students as anchors for both our literacy and our math class.

For example, a beautiful illustration from A Family Tree, by Staci Lola Drouillard features river rocks along the bank of a river. This story helps us understand the Native American Experience while providing an excellent context for a problem. I wonder - how many stones are along that portion of Gichigaming? That portion of the lake represents ¼ of a mile - if the lake is 349 miles long, how many rocks could be along an entire lake? What could impact the amount of rocks along the lake? Will that impact someone’s ability to grow plants near there? Using children’s literature as a relevant context, especially a context that relates to the world our children live in, can support engagement across multiple content areas while ensuring all students are able to think critically about mathematics rooted in a context familiar to all of them.

For example, a beautiful illustration from A Family Tree, by Staci Lola Drouillard features river rocks along the bank of a river. This story helps us understand the Native American Experience while providing an excellent context for a problem. I wonder - how many stones are along that portion of Gichigaming? That portion of the lake represents ¼ of a mile - if the lake is 349 miles long, how many rocks could be along an entire lake? What could impact the amount of rocks along the lake? Will that impact someone’s ability to grow plants near there? Using children’s literature as a relevant context, especially a context that relates to the world our children live in, can support engagement across multiple content areas while ensuring all students are able to think critically about mathematics rooted in a context familiar to all of them.

Use students’ interests to ask authentic questions

Teachers can help students engage with mathematics by using students’ interests as context to make mathematical content meaningful. Students are more likely to engage in mathematics when asked to solve problems that are relevant, realistic, worthwhile, enjoyable, and motivating. In our book, we share the story of Payton - a third grader in my class who did not feel a sense of belonging or interest in engaging in math class. Often, this looked like responding to math class, starting with an escalation in distracting behaviors. Payton did not see himself as a mathematician and did not see a point in engaging in mathematical thinking. I started paying closer attention to Payton’s interests to connect with him. I learned about his interest in fast cars like the Bugatti Chiron Super Sport, Ford Mustang, McLaren Speedtail, and Dodge Challenger. I started using photos and key facts about these cars in our launches, asking questions like - “What’s the same and different about these cars?”, “Which one would you buy and why?”. This led to discussions about acceleration rate and best features for the price. Payton started to chime into the discussion with information I had no idea about, like horsepower, torque, and gear ratios. By paying attention to Payton’s interest, which correlated with many other students’ interests in my class - I was able to engage students in a mathematically relevant conversation rooted in questions they were actually interested in pondering. Some other interesting questions have derived from these types of conversations in my class, like - “How many spools of elastic string do we need to order so each of us can make three friendship bracelets?” and “Is it better to order the super jumbo pack of washable markers at a lower price, or order the smaller sets knowing there are certain colors we need to add to our collection?” Using students' interests and experiences to ask authentic questions ensures we co-create a learning environment that is rooted in the mathematics that is all around us.

Using students' interests and experiences to ask authentic questions ensures we co-create a learning environment that is rooted in the mathematics that is all around us.

Math is joyful. Our greatest mathematicians, who spent their lives asking questions and seeking solutions, knew that a deep and lasting engagement in math in their world brings happiness, inspiration, and connection. This is the real mathematics we want our students to experience. Through the UDL lens, we are removing the barrier to real mathematics by considering our students’ interests, relevant contexts, and meaningful questions to ponder. Our goal as teachers should always be to create a space where students can share ideas and make sense of the mathematics related to their world. Using our community, children’s literature, and our students’ interests are key ways to center your students as you design math learning experiences in your classroom.